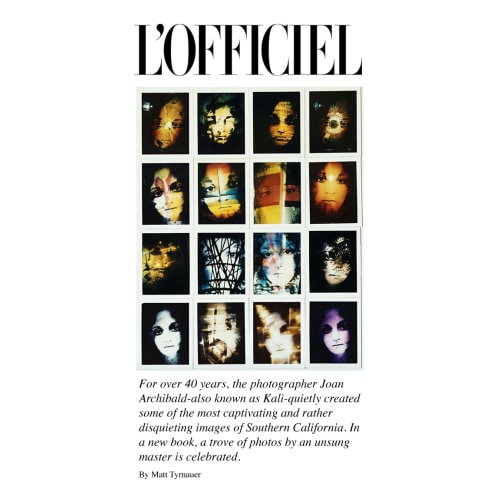

For over 40 years, the photographer Joan Archibald—also known as Kali—quietly created some of the most captivating and rather disquieting images of Southern California. In a new book, a trove of photos by an unsung master is celebrated.

I moved recently to a house in a canyon in Los Angeles, which is similar in its situation to the house in which I grew up in a neighboring foothill section of the city. Like the house my parents had, this property has views on to nearby canyon ridges. It is all quite picturesque in these canyons— as well as voyeuristic—because of views on to the backs of other canyon homes, framed by tall trees. In the distance— after dusk—there are city lights; in the foreground, coyotes. Overhead, in the L.A. canyons, with surprising frequency, there is the thunder of police helicopters. As I have not lived in an L.A. canyon for some years, the effect of returning is Proustian, being back above the city I live in, where I am from, now half remembering, half experiencing anew the microclimate of these hills. The marine layer, the same botanical perfumes wafting seasonally—orange blossom; then night-blooming jasmine; then frangipani; then sage.

This ridge, with this view and attendant memories is an especially good perch to be on as I peruse the photos in these pages you are about to explore. The photos of Joan Archibald—or Kali, as she styled herself in about 1964— evoke a deep feeling, or better yet, realization of Los Angeles, or greater Los Angeles. The photos in these volumes, for the most part, came from a similar, timelessly picturesque canyon; they were developed in makeshift darkrooms. Those that didn’t come from the garage darkroom in the nearby canyon, came from the desert, developed in a master bath darkroom in Palm Springs, to be specific.

Canyon and desert were the main environments of Kali, who, from the mid 1960s to the mid 2000s, was a secretive and therefore obscure master of the visual arts, hidden among the mostly conventional West L.A. housewives of her generation. Joan Archibald turns out to have been one the great chroniclers of the waning 20th century years of her adopted hometown; a secret historian of the era we now know mostly from the heavily marketed triumphs of The Beach Boys, The Doors, Joni Mitchell, Joan Didion, and Shampoo.

What you have in front of you is, in effect, a discovered memoir; an interior monologue in visual form. And, while thoroughly personal, the images—for the most part never- before-seen, and maybe never intended to be seen—will stir up memories and emotions for anyone who got even a peek at those hazy, dazed years of psychedelic, hippie, haywire L.A.—virtually indescribable to anyone who turned up here any time after the dawn of the ’80s.

Kali was born Joan Maire Yarusso in 1932, in Islip, New York. She married Bob Archibald, a trumpet player. He was apparently on the road a lot. Joan Archibald was divorced by the age of 30, and, according to her daughter, Susan Archibald, got in a car and ended up in the Malibu of 1962. With her good looks and some allure, she became a fixture at the beach parties of the era.

FROM AN UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF A CONVERSATION WITH SUSAN ARCHIBALD, REGARDING HER RECOLLECTIONS FROM THIS PERIOD:

Well, my mom had two children and she needed to get away and my brother and me went to boarding school and my mom needed to expand herself, whatever she was searching for, and she landed in Malibu and she was hobnobbing with Richard Chamberlain. My mom needed to find a place, through my grandmother’s guidance, because my grandmother told my mother that Malibu was not a place for her kids. After that, my mother went to Palm Springs and she bought Sandra Dee and Bobby Darin’s house. Frank Sinatra wanted to date my mom but my mom wanted nothing to do with him.

Kali took photography classes at The College of the Desert, in Palm Desert. But no one knows exactly when and how her style developed. An improvised darkroom in the master bath in the Palm Springs house started churning out 16x20 black and white prints on silver Portriga paper, semi-gloss or canvas-textured, all with rough edges. Then, after a stop bath in Sandra Dee’s Roman tub, the prints were floated in the pool; the water of the pool would become colored with Dr. Ph. Martin inks, for tints; spray developer may be applied, which could create abstraction; swirling prints in the uncleaned pool caught bugs and desert sand on the surface for texture. The prints were sun-dried on the pool deck, where more sand or bugs may have stuck to them. After this process, the prints ceased to be simply photography. They were impressionistic or expressionistic works. Kali trademarked her work: Artography (unrecorded at this point). This went along with the name change to Kali, and a recorded copyright, Kali Kolor Ltd.

Her portrait and landscape subjects, and treatment of these images, depict a serial acid trip—one she may or may not, in fact, have been on—articulated as well as anyone who ever made the attempt. Certain characters recur: Debbie, classic beauty; Susan, model, daughter; Mary, Renaissance visage; Kali, artist on the edge; Paul in the Speedo, satellite of love.

A few days into looking at the images in the Portraits and Landscapes volume, I thought I should re-read Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays. As I was reading it, and, alternately, staring at the black and white photo of the stacked freeway overpasses, and, a few pages later, the attractive couple not quite connecting, with an overlaid exposure of a menacing, atomic age motherboard of some sort, it seemed to me that Didion’s text somehow matched up perfectly. Both of the works capture the disquieting potential for the devastating mood which relentlessly fair-skied Southern California can breed—a creeping ennui verging into madness.

In the November 1970 edition of Camera 35 magazine, there was the only article ever published on the work of Kali. The article is called “Eyes By Kali,” and it ran with some of her photos focusing on young people’s eyes. “Kali is...a young woman who lives in Palm Springs, California, and creates painterly pictures for a living,” reads the text. “Her subjects range from her teenage daughter to the family cat to anything and everything that she might encounter with her camera.... Kali feels her Artography (a word she coined and has since copyrighted) is a category of visual communication complete unto itself. ... No argument there. They offer physical texture and surface modulations that are beyond the capabilities of mere machines. In fact, there is not a way to reproduce one of her images; as a result each of them is an original. Which, of course, enables her to sell them in galleries, not as photographs that can be run off in multiples, but as unique works of art.”

There was only one known gallery show of Kali’s work, which was, according to Susan, in Monterey in the early 1970s. “Ansel Adams stopped by and he saw my mother’s work and was like, `Wow, who is this person?’ Ansel Adams thought something of my mother’s work in the day.” Mostly, the hundreds of prints were tossed into storage cabinets and suitcases, never to be seen until now.

FROM THE SUSAN ARCHIBALD TRANSCRIPT:

It started in Palm Springs, which is pretty weird. In the late ‘60s, my mom would take my brother and me out in her ‘62 Studebaker and all of a sudden she would see something like going over a power line and at that time from Palm Springs to Indio, California wasn’t that built up so it was very dark. She would see these sightings and then she’d call whomever. The airport, whoever would listen to her. And they basically shunned her out.

In 1973, Kali married Karl Davis, Jr., a lawyer. They met in Palm Springs and lived at 16900 Enchanted Place, in the canyons of the Pacific Palisades. Kali set up a second darkroom in the garage, and the pool in the backyard functioned as the wash tray. Kali continued to go to Palm Springs. Kali did not stop taking and developing photos. As Karl had money there was no imperative to sell Artography. After Karl died in 2000, Kali became a quasi-shut in. The UFOs, Susan believes, had been following her mother for years in both Indio County and in the Palisades canyon. There was an uptick in the sightings after Karl died.

FROM THE SUSAN ARCHIBALD TRANSCRIPT:

Orbs, or orbies, she called them, and my mother started documenting them with the film she was shooting on the infrared feeds in the Pacific Palisades house. She was doing Polaroids of these images, which were outstanding.

Kali recorded, obsessively, the appearance of the flashes and unidentified images in her closed circuit monitors, sketched them, and made notes. The unprocessed film was discovered in a flight bag by Susan. It was recently processed, and selections appear here in Outer Space. The time codes in the journals, matched with the time codes from the infrared monitors on the processed film, give an immediacy, and insight into Kali’s late nights.

In 2017, suffering from Parkinson’s and memory loss, Kali was found wandering in the canyon near 16900 Enchanted Place. She was picked up by authorities, and placed in a public assisted living facility. Eventually, Susan was contacted, and she was moved to a private nursing home. As 16900 Enchanted Place was being cleared of her belongings, all of the photos in these volumes were discovered. On January 14, 2019, Kali died from complications of Parkinson’s disease. She was 87.

Since the discovery of the photographs of Vivian Maier, and the posthumous publication and celebration of her work, the thrilling prospect of finding other unknown masters of the art form has more than ever been in the back of many an aesthetes’ mind. The particular excitement derives from the utter improbability that there could be complete archives of unsung masters out there. Maier, after her work was posted on a Flickr account, became a viral sensation, and was quickly appraised to be the equal of Diane Arbus and Robert Frank. Kali herself seems to be a different kind of rare breed. The record shows that she started to get some recognition for her work, but then retreated. Was she insecure? Distracted? Comfortable in her identity as the wife of a lawyer? Or was it the sexism of the times, combined with the lack of seriousness attached to the art of photography?

We will never know for sure. But one of the key standards of artistic judgment is the so-called test of time. In that regard, the delayed discovery of Kali’s complete works, long shuttered in her scattershot archive, may have been a favor to everyone—and Kali, most of all. Her ’60s and ’70s work is evocative of its time. Much of it looks like the Age of Aquarius, and if it had been widely known at that time, it may have been judged as dated by the time the go-go ’80s had set in. Tie-dye shirts and VW busses were something to snicker at when I was in middle school. But, by hiding her work, Kali, intentionally or not, avoids any charge that her skill—I’d venture genius—can have been diluted by having the “fashion of the day injected into it to gain wider acceptance,” as a critic once defined the main demerit of the test of time standard. We can, as these pages prove, better appreciate, and, yes, judge the work of Joan Archibald, aka Kali, at a distance, and, in what amounts to a catalogue raisonné, better appraise the depth and breadth of her work: The architectural and landscape photography, the portrait work, the high Artography of the hippie era, and, finally what herein is grouped as “Outer Space.” Viewed all together, it’s an astonishing, coherent oeuvre, with marked stylistic shifts and distinct periods. Kali vs. the test of time.

An excerpt of Matt Tyrnauer’s foreword for Kali Ltd. Ed. by Len Prince, published by powerHouse Books.